In 1954, the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision officially declared segregation in public schools as unconstitutional. All U.S. public schools were instructed to integrate. Within a week, Arkansas was one of two Southern states to announce it would begin immediately to take steps to comply with the new ruling. The Arkansas Law School had been integrated since 1949, and by 1957, seven of Arkansas’s eight state universities had desegregated. Blacks had been appointed to state boards and elected to local offices; however, public state high schools were a different story.

In September of 1957, the public school ruling was tested for the first time when in Little Rock, nine black students enrolled at the previously all-white Central High School.

Dr. Barclay Key, Professor of History at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock, first provides an astonishingly vivid history of the civil rights movement in Arkansas, including the case of the brave young students who became known as the “Little Rock Nine.”

We next hear Amber Smith, Director of the Charles W. Donaldson Scholars Academy, about this place-specific pipeline project which works with underrepresented students to create college expectations and preparedness through bridging and support programs. Students who would otherwise place into remedial coursework upon entering college receive “bridging” instruction the summer prior to their first semester.

One of our panelists is none other than Dr. Charles Donaldson himself! He shares his personal passion for this project, what makes the program work, who it seeks to serve, and the scaling challenges that keep him up at night.

Charles W. Donaldson Scholars Academy Presentation

As I reflect on what this part of the trip meant to me, I think my thoughts are best summed up by something a fellow travel companion mentioned. After the Donaldson Scholars Academy presentation, someone said their hope in our education system faded the further they moved along their own educational journey. In other words, the more they learned about how broken our K-20 pipeline is, the less they though they could fix it. And yet, hearing how hard Dr. Donaldson, Amber, and their staff work towards changing the higher education prospects of their participants, the more I am reminded of why I remain committed to the field of education. The stories they shared of their students and their success were touching and reminded me of how so many of my childhood friends were easily brighter than I and yet had an entire system of education working against them. The work of the Donaldson Scholars Academy confirmed my desire to learn more about college access programs and the organizational processes that make them successful in serving historically underrepresented students.

Beyond confirming my desire to expand access to higher education, Dr. Donaldson and his team reminded me how important it is to consider the manner in which we work toward that goal. Each person that presented, from the student turned staffer to Dr. Donaldson himself, displayed such a sense of utter selflessness and humility. Titles, job descriptions, salaries, these things meant nothing to them. All that mattered was their mission to improve educational attainment for all students and prepare students for success in and outside the classroom. As graduate students and higher education scholars, we do not always get the opportunity to show this kind of humility and sense of commitment to the advancement of others. Nevertheless, hearing from this group reminded me how important it is that we create such opportunities for ourselves, so that we do not lose sight of why we are in education in the first place.

–Christian A. Martell, doctoral student

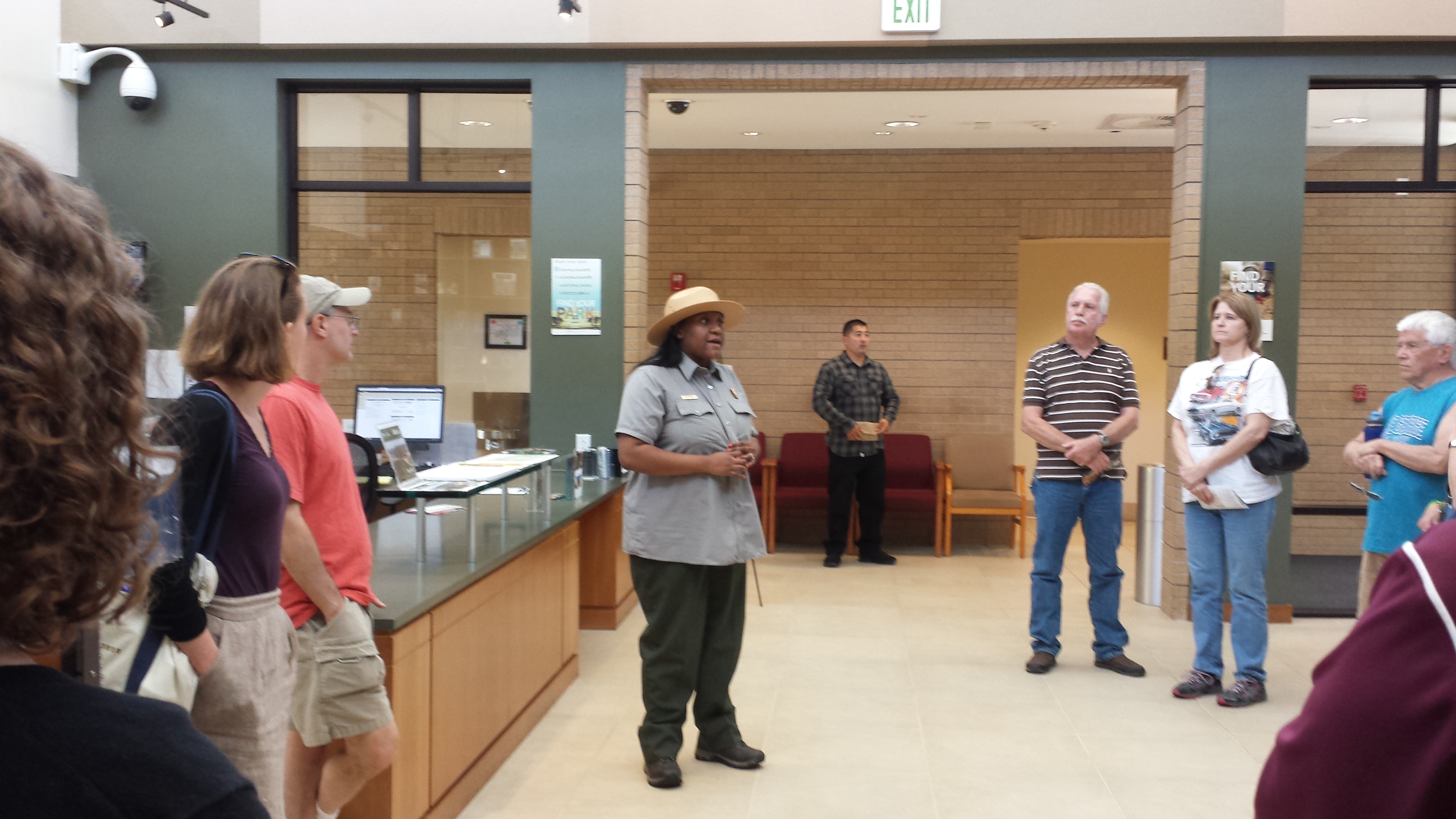

At the recommendation of Dr. Greg Barrett, Professor of Higher Education at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (and proud PhD alumnus of CSHPE!), we take the National Park Service tour of Little Rock Central High School. We are not disappointed.

Central High School

Similar to our trip to the Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel, visiting Central High School allowed us to see a part of history I had only read about or seen in clips from documentaries. The National Parks Service has done an excellent job of preserving the space for learning and engagement with the past. The school building strikes a regal figure, looking more like a castle or European university than a high school. With a reflecting pool, Greek inspired columns, and a high tower, the grandeur of the building must have a communicated dominance over outsiders, then the Black community of Little Rock. The vivid tour guide provided context for why only nine black students came to Central High School in 1957; over hundred others had been intimidated not to enroll or judged not a good fit for the school. Despite threats, Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Thelma Mothershed, Melba Patillo, Gloria Ray, Terrence Roberts, Jefferson Thomas and Carlotta Walls integrated Central High School on September 24, 1957.

The U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division, a unit whose previous mission had been fighting the Nazis, were deployed to enforce the law and protect the students. I wonder what the students and their military guards made of that arrangement.

Our tour guide frequently emphasized the Little Rock Nine were told they had to be non-violent while attending school. Even with military officers, their White classmates harassed them constantly and violently, hoping to get them expelled for reacting. Only one student, Minnijean Brown, was expelled for verbally responding to a group of girls who threw a purse full of locks at her. The following year, the governor of Arkansas shut down all the high schools in Little Rock for a year, preventing Black and White students from continuing their studies. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. comparison of racism to poison is quite apt here. Instead of integrating the schools, the White establishment in Little Rock destroyed educational prospects for everyone to maintain the racial power structure.

I left Central High School inspired, yet sad. I never got the whole story of the Little Rock Nine until this trip. Learning of the abuse, harassment, and denial of education by the state for claiming their rights increased my respect for their sacrifice. The early students who took the first steps into White only schools across the country endured traumas I can only imagine. In talking with people about Central High School today, we learned the building is basically re-segregated through tracking and AP courses. On the upper floors, predominantly White students attend their college prep courses, with students of color attending school on the lower floors. Reflecting with the group, I started thinking about the goals of Civil Rights Movement and integration. It wasn’t to simply share the same physical space, though physical space was used to demarcate privilege and opportunity. The goal was for the same opportunities and dignity as persons in their community to advance their lives. Even though Central High School and other institutions of education are integrated, there is much more work to be done to realize that goal for equitable and inclusive educational experiences for students of color.

–Kamaria Porter, doctoral student

In the evening, our group enjoys dinner with fellow CSHPEers (and resident experts!), Dr. Greg Barrett (PhD ’02) and Kelicia Hollis (MA ’14).

At the recommendation of Greg Barrett, we stop by the State Capitol to take a solemn and reflective walk around the grounds near the Little Rock Nine sculpture–bravery frozen in time for visitors. What have we learned from their efforts, and those of others over the past half century? One sobering fact provided at the start of the day by Dr. Key is that where people live in Little Rock is more racially segregated today than it was in 1957. It has been an emotional day!

On a lighter note, the next morning we explore the lovely Little Rock river front and take in the farmer’s market.

We visit the Clinton Presidential Library in the afternoon before heading toward our next stop, Jackson, MS.

Clinton Library

We concluded our trip to Little Rock with a visit and lunch at the Clinton Presidential Library. I remember, though vaguely, the Clinton Presidency and it was interesting to see recent history memorialized before me. I read some of the letters between Clintons and luminaries like Mother Teresa and Paul Newman (personal favorite). Looking at the daily agendas of President Clinton, I was struck with the schizophrenic nature of the role. The need to be in the constant motion and interaction with people and problems, always moving on to the next thing. The election process doesn’t really educate us about the presidency, nor does it highlight capacities needed for the role in the vetting process.

The space is designed to laud the accomplishments of Clinton, glossing over his faults and negative consequences of his administration’s policies. The Library, similar to the state capitals we visited, tries to preserve a political history in the best light, leaving things we would rather not discuss in the dark. I wonder how we will actually learn from the past if we don’t let ourselves see it all at once.

As a fan of The West Wing, I got a kick out of being in the Oval Office and Cabinet room replicas. A few in our group took grad photos at the president’s desk. While there, I thought about leadership and community. While not aspiring to be president, I know everyone in our group hopes to lead efforts to improve the education experience for students and promote social justice. I felt grateful to have made connections with my co-travelers and I hope we can achieve those goals together, pooling our knowledge and perspectives as we did during the trip.

–Kamaria Porter, doctoral student