On Monday morning we visited Pontifica Universidad Catolica, or Catholic University, which is one of the eight universities that existed before 1980 in Chile. Catholic University is one of the most prestigious universities in Chile, along with the University of Chile, and is home to the Center for Research on Educational Policy and Practice (CEPPE-UC). We met there with Andres Bernasconi, who wrote one of the articles we read in preparation for our trip to Chile, in addition to several other well-known scholars who study higher education in Chile.

On Monday morning we visited Pontifica Universidad Catolica, or Catholic University, which is one of the eight universities that existed before 1980 in Chile. Catholic University is one of the most prestigious universities in Chile, along with the University of Chile, and is home to the Center for Research on Educational Policy and Practice (CEPPE-UC). We met there with Andres Bernasconi, who wrote one of the articles we read in preparation for our trip to Chile, in addition to several other well-known scholars who study higher education in Chile.

We have heard again and again that there are very few scholars in Chile—only a handful—whose focus is the higher education level, as opposed to primary and secondary school education. Andres, Magdelena Jara, and other scholars shared with us the role and structure of their Center and more about the Chilean higher education system in general. In particular, they explained the reward and recognition system for faculty, which is based more on status similar that of a civil servant than the US tenure system. We also heard of the need for faculty to publish in journals written in English, even though that means articles are less likely to be read in Chile. As a result, articles are often translated into Spanish and circulated through bulletins so that the information can be disseminated among Chilean scholars as well.

A few of the commonalities between the US and Chilean higher education systems we heard include the following:

- “You’re starting to see in Chile the bifurcation of the profession now,” Andres told us, referring to the divide between academics and administrators.

- Push in Chile now for professors to have a PhD at the prestigious universities—Catholic University is now requiring both teaching and research of its full-time faculty.

- A council of rectors (the rector position is similar to a university president in the States) from 25 of the higher education institutions in Chile meet periodically with the Ministry of Education and play a role similar to that of the Presidents’ Council in Michigan.

When we asked Andres what he considers the greatest needs of future research around higher education in Chile, he described the following areas:

- Access and affordability (Another topic we have heard discussed during every visit on this trip)

- Community colleges and technical training institutes, including the current connection between secondary schooling in Chile

- Higher education management and change, which is Andres’ area of research. He told us that the system is “private in totality with a few public minority entities,” which has forced institutions to adapt to the marketplace.

We were welcomed by the Dean of the School of Education during lunch provided by Catholic University. The Dean expressed that he was impressed by the wealth of our backgrounds around the table, from undergraduate study in English and political science, to mathematics and neuroscience.

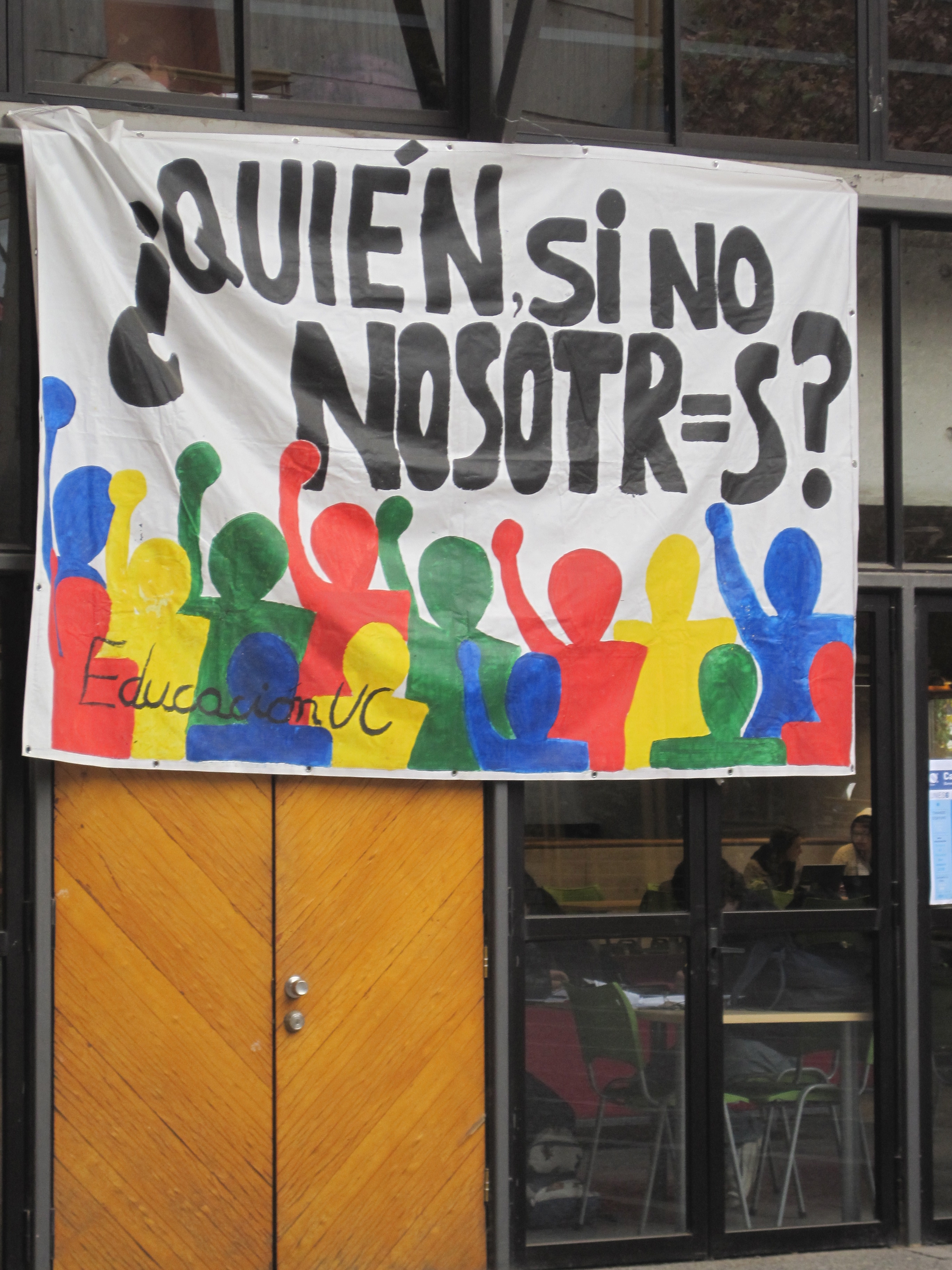

After lunch, we split into two groups, with one visiting AIEP, the largest professional institute in Chile. The other group visited Universidad Alberto Hurtado, a new university founded in 1997. Alberto Hurtado was built out of a research center, CIDE, focused on social issues, which continued to exist through the military regime. After democracy returned in the early 1990s, Fernando Verdugo, the Vice President for Integration there, told us that community of researchers asked themselves, “What can we contribute to this changing society?” With their identity also as a Jesuit community whose focus was on creating a more integrated society that promotes pluralistic academic dialogue, CIDE decided to develop into an undergraduate university.

Today Alberto Hurtado is located in the center of the city and has partnerships with universities around the world, including offering dual degrees with universities in the U.S. The university focuses on improving access for students from lower SES backgrounds. Fernando and Isabel Donoso Ureta, the Coordinator of International Programs, shared with us that only 25% of students at Alberto Hurtado come from private schools, whereas 55% come from private subsidized schools, and 25% come from public schools. In several of our meetings with institutions during our visit, colleagues have told us, and shared data that demonstrates, how Chilean society continues to be stratified, which influences issues of access. Including such a high number of students from outside private secondary schooling is unusual for a university of Alberto Hurtado’s rigor and reputation.

At the end of our discussion with Fernando and Isabel, Isabel took us on a tour of part of the Alberto Hurtado campus, including to the top floor of one of the classroom buildings so we could see the sun beginning to set against the backdrop of the Santiago skyline and mountains beyond the city.